Mindanao ikat traditions belong a larger body of weaves of tie-dyed textiles in Southeast Asia. Common motifs demonstrate shared knowledge not only in techniques but also in their worldviews through their patterns and beliefs associated with weaving.

We know, for example, tha the Tbolis of the Philippines are regarded as dream weavers. They translate into weavable patterns the images and experiences they have received in their dreams through the visits of Fu Dalu, the goddess of the abaca (Musa textilis). Parallel traditions are also observed in the Iban weavers of Pua Kumbu in Sarawak, and in Indonesian ikat weaving found in the islands of Sumba, Flores, and West Nusa Tengarra.

The use of abaca, however, is unique as Mindanao ikat weavers and the ikat weavers of a southern island in Japan are the only ones known using the material in their weaves. Hence, Mindanao ikat have a special place in the family of broader Southeast Asian ikat categories.

Examining a mid-century specimen of Tbalak with the late textile collector and curator Floy Quintos. The item with minute patterns is in the collection of the author

Philippine ikat traditions are spread out across the archipelago, with most textiles being produced in Mindanao. Before, diving into the indigenous groups that make them, it is important to note that there have been ikat traditions that are threatened if not have gone extinct.

One of them is the Gompak Pulaw ikat of the Subanen in Zamboanga peninsula where extant examples are now largely found in museums and private collections. The last weaver passed away several decades ago. In the north, up until a few years ago, Candon in Ilocos Sur still had its last ikat weaver making the Inuwes, a burial cloth made specifically for one indigenous group in the Mountain Province.

Documentations on these two traditions are very scarce, and there seem little interventions made to rekindle them. It is also important to know that the oldest retrieved warp ikat specimen in Southeast Asia is the abaca Banton burial cloth, recovered in Romblon and is now on display at the National Museum of the Philippines.

Tnalak of the Tboli (South Cotabato)

Tnalak is a scared textile woven by a select few women in Lake Sebu who traditionally receive the patterns of their weaves from their dreams. These dreams reflect their core values, understanding of the universe and human relationships, and respect for their environments. The highest expression of tnalak weaving is seen in the most valued blankets called Ye Kumo.

The Late National Living Treasure Lang Dulay have helped in the documentation of more than 100 patterns and have jumpstarted the revival and promotion of tnalak to a wider audience.

Presently, master weavers such as National Living Treasure Barbara Ofong are safeguarding the tradition by teaching the younger generation of the cultural and practical importance of this textile, as well as in protecting it from improper commercialization.

Photo from our partner weaving group in Lake Sebu

Inabal of the Tagabawa Bagobo (Davao del Sur)

Inabal are considered prestige items among the Tagabawa Bagobo.

They are, for example, considered to provide a blanket of protection to a household. The late National Living Treasure Salinta Monon was the last of her generation to practice the weaving of this ikat tradition. She was known to be one of the few who could execute the most difficult pattern, the sacred binuwaya (crocodile). Though not as well known as the Tnalak of the Tbolis, inabal is equally sophisticated in design and production.

An inabal woven by one of the current master ikat weavers of Bansalan in Davao del Sur who learned from the late National Living Treasure Salinta Monon

Mabal Tabih of the Blaan (Davao del Sur)

The production of Mabal Tabih has similarities to that of Tnalak, but some patterns produced are finer, and the design fields are denser in motifs. Natural dyes are being used in the process, and the best expressions of this weaving tradition results in their exquisite tubular skirts.

The late National Living Treasure Yabing Masalon Dulo is considered as one of the best culture bearers, not only in weaving but also in other cultural expressions such as traditional healing.

A special kind of tabih is the one that is redder in color. The family of the late master weaver was able to inherit the knowledge and they continue the tradition to this day.

Participation for on-site weaving during the 2005 MunaTo Festival with her students. Photo by IPDP.

Tabih is now gaining more popularity and is becoming more accessible thanks to the growing number of present-day weavers that the community has.

Dagmay of the Mandaya (Davao Oriental)

Traditionally, dagmay is woven using abaca, but there are also old samples that are woven using cotton. One of the few remaining masters who can execute dagmay in both medium is National Living Treasure Samporonia Madanlo.

Sharing strong similarities with Tnalak and Tabih, dagmay differs in that it is not polished in the final stage of production, yielding to a coarser textile.

Another exceptional feature of dagmay is that it is able to represent anthropomorphic figures in their patterns – a tradition not observed in other Mindanao ikat.

The human figures are highly revered as they are said to honor ancestors of the Mandaya. The reptilian motif is equally considered as a highpoint of their cultural expressions in weaving.

Image courtesy of Philippine Star – “Mandaya and modern artistry in Lanang” (2014)

Source

Biyaludan of the Iranun (Sultan Kudarat and North Cotabato)

One of the most sophisticated among the various categories of Iranun weaving (they are also proficient in supplementary weft weaving), biyaludan was traditional woven using silk which ties the weaving tradition to the maritime Silk Road.

Today, the more available material rayon is used as the alternative. The iranun expresses the biyadulan mostly in their tubular skirts called malong.

Compared to their previous ikat traditions mentioned, the Iranun does not exhibit horror vacui, or the fear of empty spaces in their weaves. Biyaludan is also called binaludan, the term used by the Meranaw people for their ikat weaves.

Binaludan of the Meranaw (Lanao del Norte and Lanao del Sur)

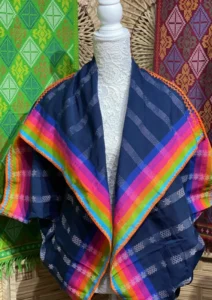

The binaludan of the Menaraw are some of the most colorful ikat traditions to come out of Mindanao. They go beyond the trinity of colors (red, black and natural hue of the abaca) that the other weaving traditions observe. Aside from warp ikat weaving, they are also adept in weft ikat weaving, a trait they share with the Iranun.

A special technique that the Meranaw have combine the two ikat techniques resulting in what is called double ikat which can be appreciated in their most prized malong called malong aandon.

The elusive malong aandon traces its origins to the Patola weaves of Gujarat in India. Often laid out in vertical strips, the balud patterns are also unique, where the older specimens feature more elaborate designs and motifs. Binaludan comes out in their malong, blankets and lalansay (draperies backdropping the most important walls of the royal abodes called torogan).