The Yakans

Originally from the southern island of Basilan, the Yakans are an indigenous people with a rich cultural history. Considered to have one of the finest weaving traditions in the country, Yakan tenun has gained immense popularity when some of them moved to the Zamboanga peninsula, giving them closer access to a wider audience.

Yakan tenun weaving embraces a wide repertoire of techniques ranging from the basic bunga to the complex sinaluan. Their intricate headscarf called seputangan is a prized item. A lot of colors are put into the patterns, and no space is left empty in the textile. While it appears to bear floral patterns, it does not. When the minute details of the seputangan are broken down, it reveals that what looks like a flower is in fact a montage of several patterns symbolizing mountains, grains, ladders, the eyes, among others (Pasilan, nd).

Sumping-sumping (Yakan Flower)

According to the descendants of the late National Living Treasure Awardee Ambalang Ausalin, the Yakans are not as abundant as the Ilocanos in the use of floral motifs. They use abstract geometric patterns instead. However, there is one exemption: the sumping-sumping. As the only floral motif to come out of the Yakans, the sumping-sumping does not even represent or imitate any real flower; hence, it is still considered to be an abstract figure.

The sumping-sumping bears similarities with the Ilocano bulbulala in a way that is a basic pattern composed of petals radiating from a central point. While the bulbulala has a curved edge, the sumping-sumping has a pointed one. When Ausalin was still alive, she shared what she believed is that the closest real-life flower that the sumping-sumping may represent: the flower of the cosmos plant (Cosmos bipinnatus) that grows abundantly in their weaving village in Lamitan City. It is interesting to note that the cosmos plant comes from Mexico, and weavers of Mexico also have a pattern that closely resemble the sumping-sumping.

A further investigation may be needed to explore possible connections.

Figure 3: The late National Living Treasure Ambalang Ausalin weaving an inalaman with sumping-sumping, and a cosmos flower

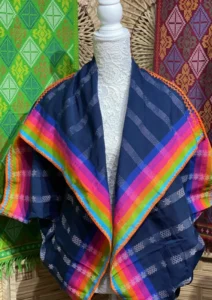

The sumping-sumping usually occurs in bunga weaves, as well as in an inalaman and a pinalantupan, both of which are traditionally used by Yakan women as waist covers. The sumping-sumping can be made using just one color, or having each of its petals bear different colors. It can also be the case wherein in one petal, various shades of a color can be used, suggesting the impressive color sensitivity and penchant of the Yakan weavers for producing vividly colorful textiles.

The Blaans

The Blaans are known for two traditional woven art: the mabal tabih, an ikat weave using abaca (Musa textilis), and the igem, a mat weave using pandan leaves (Pandanus amaryllifolius). The mabal tabih bears uncanny resemblances to the ikat traditions of the Tbolis and the Bagobos, heavily donned with abstract patterns depicting nature and animals. According to ikat weavers from the Blaan, Tboli, and Bagobo groups, there are no floral patterns known to them. However, in igem mat weaving, there is a pattern that is indirectly associated with a flower.

Figure 4: Yakan Sumping-sumping in a purple inalaman, and Blaan Dak sina

Dak sina (Blaan Toy/Flower)

One of the most iconic patterns to come out of igem weaving, which was popularized by National Living Treasure Awardee Estelita Bantilan of Sarangani province, is the dak sina. The dak sina pattern is laid out in two colors, the neutral hue of dried pandan leaves and the black naturally dyed strips of the same natural material.

Although it appears like stars, the dak sina is said to be inspired by a Blaan toy made of folded palm leaves. This toy looks like a wind spinner, but it is not as it is never used as such by the community. It simply is a four-armed work used as a décor or as something that the Blaan children would use during their plays.

When asked about the inspiration of the toy from which the dak sina is based on, Lorcita Bantilan, the daughter of Estelita Bantilan, shares it is meant to represent a flower, i.e., that the toy imitates a flower, and the toy in turn is the basis for the dak sina pattern. Therefore, the dak sina is indirectly a representation of a flower (2022).

Philippine Weaves: A Situationer

Philippine weaving is currently seeing a massive revival not seen since the post-war. The darkest period in Philippine weaving would be in the 60s to 70s when economic shifts were happening, propelling weavers to abandon their craft for more profitable pursuits. This was also the time when Philippine cotton production has plunged deep to near extinction.

The weavers who stayed with the craft, unfortunately, resorted to using cheaper, most accessible alternative materials such as polyster-cotton blends and pure polyester threads from China (Guerrero, 2021). Despite the Renaissance that the Philippine weaving is experiencing, what has been lost are the traditional meanings attached to these works and their patterns. The drive for weaving nowadays is largely commercial, rather than as a means of expression for and by the artist-weaver.

The vast number of textiles being produced today only suggests that many are being trained to produce sellable template patterns, repeated over and over again. The master weavers, on the other hand, those who are skilled enough to produce, modify, and reinterpret patterns and designs, are being left behind with little incentive to continue with the real spirit of traditional weaving that yields to rare and unique master works. The thinning number of old master weavers is concerning as it may mean the loss of older patterns that have neither yet been documented nor reproduced recently.

Another problem arises when weaving, as a potential source of livelihood, is being introduced carelessly to communities that do not have a history of weaving. The issue arises when patterns specific to one community and is held by that community as uniquely their own is being taught to another, as this blurs the lines of cultural identities and their boundaries. “The rise of low-cost handwoven textiles in the market lately, on the other hand, got me more concerned than ecstatic.

The quality is not like what it used to be anymore. Nowadays, loosely woven inabel blankets, for example, are being produced in a factory-like speed using inferior threads. Naturally, sellers compensate this with dazzling marketing gimmicks. Stiff competition has even led to some Yakan patterns being copied somewhere else only to be sold off as ‘Yakan-made,’ making us wonder if they could still be considered authentic.” (Guerrero (b), 2021)

Works Cited List:

Guatlo, R. (2013). “Abel Iloco,” in Habi: A Journey Through Philippine Handwoven Textiles. Manila: Vibal Publishing House

Guerrero, B. (2021). “Sinukitan: Research and Documentation of the Supplementary Weft Handloom Weaving in Paoay, Ilocos Norte.” Baguio City: Museo Kordilyera, Corditex Project

Guerrero (b), B. (2021). “Philippine Weaves: A Collector’s Journey”. Makati City: Tony & Nick , BusinessMirror

Pasilan, E. (Nd). “Ambalang Ausalin”. National Commission for Culture and the Arts. Accessed 20 July 2021, https://ncca.gov.ph/about-culture-and-arts/culture-profile/gamaba/ambalang-ausalin/

Pastor-Roces, M. (1991). “Sinaunang Habi: Philippine Ancestral Weaves.” Manila: Kyodo Printing Company

Respicio, N. (1996). “Abel ti Amianan,” a handout in the Sulyap Kultura II Exhibition of the Northern Philippine Textiles. Manila: National Commission for Culture and the Arts

Valmonte, J. (1988). “Textile Industry of Ilocos (1758-1819),” a paper in History. Quezon City: University of the Philipppines Diliman