Binakol is one of the most iconic inabel weaving traditions to come out of the northern Philippines. It is easily distinguishable for its minimal use of colors –most of the time utilizing only two tones– and its highly precise warp and weft counting that results in various patterns that are so desired today as it was back in the past.

Binakol as a Shared Tradition

Binakol may have come from the Ilocano word, binukel, which refers to the creation of circles and spheroids. The most popular binakol pattern is the kusikos (Whirlpool-like). It has been observed that while both the lowland and upland northern Philippines culturally share the binakol, it has been shown that lowland weavers have a penchant for creating smaller circles. In a regular 18-inch width textile, for example, they can fit as much as eight to nine kusikos. One esteemed weaver who can accomplish this is the centenarian National Living Treasure Magdalena Gamayo from Pinili, Ilocos Norte.

The researcher with Manlilikha ng Bayan Magdalena Gamayo weaving binakol with the kusikos pattern

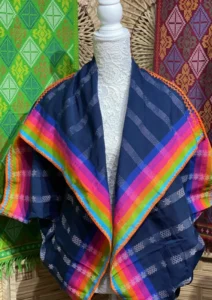

The weavers of Abra and Ilocos Sur, on the other hand, have a higher propensity in using more than two colors in their binakol, creating more vibrant and colorful permutations. Older binakol specimens from the Tingguians, mostly in the form of ules (blankets), are embellished with embroideries of their highly-prized symbols such as the frogs, rice stalks, and footprints. The weaving communities of Paoay exhibit a wide range of interpretations of the kusikos. Some binakol are lined, while others are partitioned in a grid-like manner. This seemingly creates boundaries among the circles. The town of Sarrat has even made binakol their specialty product, so much so that their festival is dedicated to binakol weaving. The binakol of the latter two towns are observed to be thicker and denser than others.

An antique upland three-panel handspun cotton binakol blanket with hand-embroidered joineries

Simple and Complicated at the Same Time

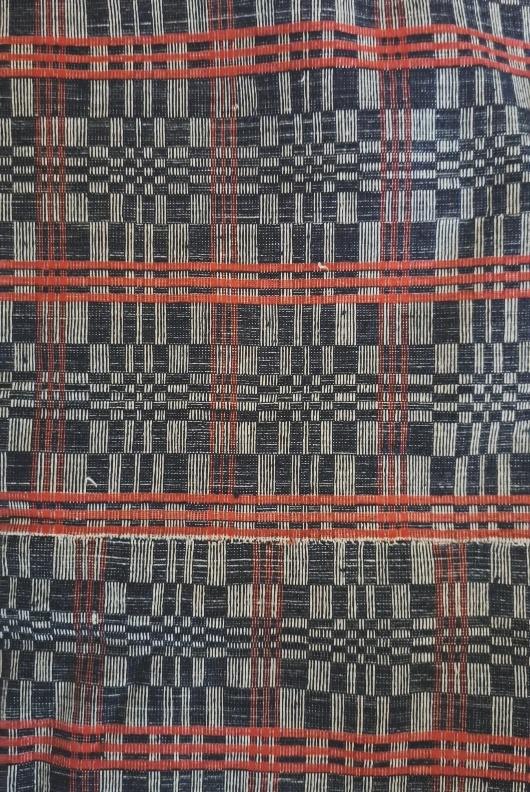

In terms of the weaving technique used, creating binakol is not the most complicated. In fact, it falls under the category of plain weave, where only two heddles and two pedals are used. This makes it simpler than multi-heddle weaves such as kundiman and binnetwagan, or supplementary weaves such as pinilian and sinukitan. Despite being a plain weave, what separates binakol from others that belong to the same category (i.e., stripes, plaids, etc.), however, is that it employs a meticulous process of counting threads, carefully arranging the warp threads in the right order, and making sure the weft threads are positioned to intersect with the warp threads at exactly where they are intended to meet. A slight miscalculation by the weaver can spell a big difference as it will inevitably avert the textile from achieving the well-balanced optical illusion the binakol is known for. Those with trained eyes can easily spot an error in the weave. As a rule of thumb, the value of any binakol lies on the symmetry and consistency of its mathematically-precise patterns throughout the textile.

There have been two schools of thought regarding the history of binakol. The most accepted and well-known is the narrative that it is as old as the tradition of inabel weaving itself. This theory posits, therefore, that the binakol is an example of a pre-colonial artform. The other school of thought suggests that the optical illusions that the binakol possesses are not unique to the Philippines, and that their origin may be traced back to the American missionaries who came to the country in the early 1900s and introduced it. Despite the opposing views on its origin, there is no denying that the Ilocanos and the Tingguians have been weaving them in their own images and have closely attached the textile to their lives and identities. The cultural attachments are more than enough to call the binakol an Ilocano and Tingguian art and is, therefore, part of the bigger Filipino story.

Another old binakol blanket with a unique pattern, superimposed with red lines in plaid configuration

In some cultures, the binakol is believed to ward off evil spirits as it makes them dizzy due to the illusions the binakol –especially the kusikos— generates. Traditionally, they were draped outside the house beside the door to prevent the evil spirits from getting in. In the uplands, they have been used during important social ceremonies. While largely made into three-panel blankets, they were also used as body covers such as stoles and capes. There are also some photos showing that binakol blankets were used during funeral practices. In the lowlands, the Ilocanos also reserve the use of binakol as special blankets/bed covers, and as table covers for solemn days of commemoration such as All Soul’s Day or anniversaries of departed ones. Some also prefer to use them as mats on the floor where elderly women would sit on for their prayers during those events.

A binakol blanket draped beside offerings to the dead during Paoay’s Tumba (Nov. 1st Tradition)

The “Other” Binakol: A Rich Tradition

Although the most commonly-known pattern to come out of binakol is the kusikos, and oftentimes they are mistakenly used interchangeably, it must be clarified that the two terms are different. Binakol refers to the classification and technique of inabel weaving, while kusikos is one of the patterns generated from that weaving technique. Technically, binakol, therefore, is not a pattern, but is a kind of inabel.

Other patterns generated using the binakol technique includes the following: sinan pal-id (fan-like), sinan ikamen (mat-like), sinan crus (cross-like), sinan tugot ti pusa (cat’s paw-like), sinan kajon (box-like), and sinan-kinelleng-kelleng (parcels of farmlands-like). There are endless permutations in creating these traditional patterns where weavers can render them in varying sizes or in different colors. Some include the vertical and/or horizontal lines that break the design fields, while others can even use mixed media like those that use bonel threads alongside pure cotton or polyster-cotton blend threads. The most sought after among collectors would be those made of handspun cotton and colored using vegetable dyes.

Old binakol blankets. Clockwise: sinan sabong (flower-like), sinan tugot ti pusa (cat’s paw-like),

and sinan pal-id (fan-like) patterns.

The binakol embodies the intersection of art, culture, and spirituality among the Ilocanos and the Tingguians. Its intricate designs not only showcase the technical skill of the weavers but also reflect their rich worldviews and deep understanding of things around them. As efforts continue to preserve and promote this tradition, binakol remains a vibrant symbol of the Filipino people at large.